Located on the south bank of the river Mandovi, upstream from the capital Panjim, Old Goa is today a site of tourist consumption for the best part of the year. From a sea of palms rise a few majestic buildings, set on the lawns that typically denote a site protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Mostly churches and convents, these monuments are usually thronged by tourists and those catering to them. The only relief is during festive occasions on the Catholic calendar, when worshippers may outnumber the tourists. But even this worship gets sold as a tourist attraction.

This is of course not all that remains of the Cidade de Goa, reputedly one of the biggest global entrepôts of 500 years ago, and the heart of the Estado da Índia, the Portuguese maritime empire that stretched from the African coast to Japan. There are many ignored remains of the old city getting weathered away in the groves (Wilson 2015), and crying out for excavation before they disappear. There is also much that is scattered all around Goa and even beyond. The capital of the Estado was a huge place, in terms of space, wealth and importance, and it is no exaggeration to say that it continues to exert its influence over the Goa of today.

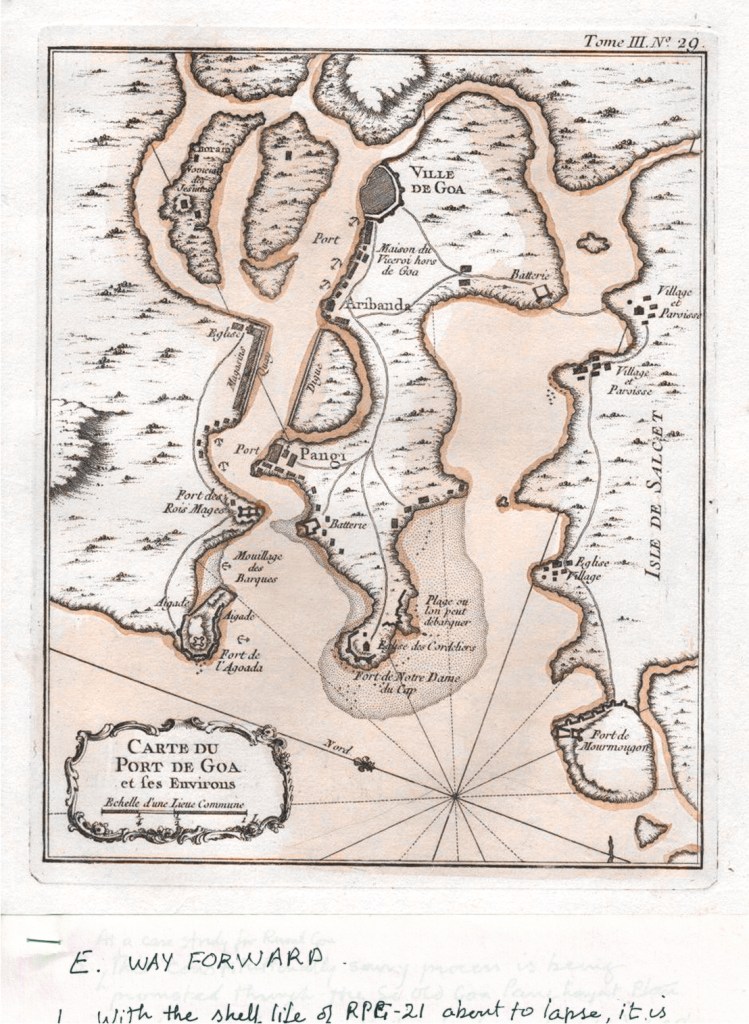

The city was born before the Portuguese arrived here, but it was as the capital of their mercantile empire that it became celebrated as the Rome of the Orient, a title that reflected two somewhat contrary pulls—the classicist and humanist movement of 16th-century Portugal, and also the city’s growing importance from the early 17th century as the centre for Christianity in Asia (Malekanthethil 2009). The 16th century was the Portuguese century, when their caravels roamed almost every ocean of the world and connected ports and people like never before. It was also the heyday of the City of Goa, when big ships would dock at the city’s harbour, and as many as seven markets flourished in the city, along with a vast number of Catholic institutions. But a slow decline in both empire and city started soon afterwards, and the capital was formally moved to Panjim in 1843.

The small group of protected monuments that stand here today are Goa’s premier tourist attraction and also feature on the UNESCO World Heritage List. They are a magnet for Catholics from Goa and beyond, especially on festive occasions like the annual feast of St. Francis Xavier. But this popularity is deceptive. Priceless heritage is actually disappearing by the day because of the pressures of so-called development and an uncaring administration. It may not be long before there is nothing that remains of this heart of the imperial era that gave birth to the modern world.

Three ships captained by Vasco da Gama launched the Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean, landing on the Malabar coast in May 1498. The plan of the newly Christianised kingdom of Portugal, under the king Dom Manuel, was to find ‘spices and Christians’, that is, Christian allies who would help them finish the ‘Moors’ (i.e., Muslims) in trade and also in the Holy Land. Added to this was the ambition of ousting Venice (the trading ally of the Moors) as the premier supplier of Eastern spices to Europe (Subrahmanyam 1997).